Loggerhead turtles Bambi and Antioche

As part of the Argonautica project, the trajectories of young loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) through the ocean have been studied using Argos transmitters (framework partnership agreement between the La Rochelle Aquarium, CNES and the French Biodiversity Agency in charge of protected marine areas).

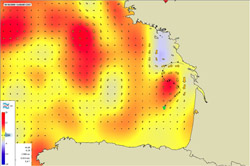

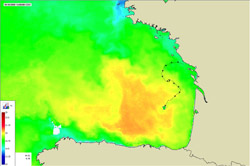

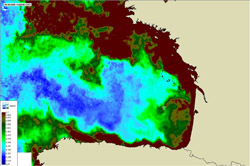

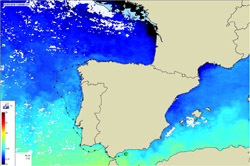

Animations showing Bambi's trajectories relative to sea level anomalies (altimetry), surface temperature (infrared) and water colour observed by satellite (click on each image to see the animation)

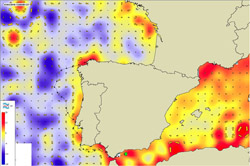

The ocean's influence on the turtles' trajectories may be highlighted by superimposing them on oceanographic data maps.

.

The loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) is a marine species in danger of extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List. It can be found in many areas, including both temperate and tropical regions of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. In the North Atlantic, their major egg-laying sites are along the United States' eastern coastline and on the Cape Verde Islands.

The loggerhead turtle's life cycle is complex. In the North Atlantic, newborns leave the American beaches where they hatched and begin their journey out to sea, between the Gulf Stream and the southeast coast of the United States, and between the Loop Current and the Florida coastline in the Gulf of Mexico. Young turtles can spend several months in waters near hatching sites or be carried offshore by ocean currents in the Gulf of Mexico and the North Atlantic.

The oceanic juvenile stage begins when young loggerheads enter the oceanic zone and drift in its gyres. A few years later, they leave the oceanic zone to move closer to the coast. The turtles develop a loyalty towards a particular feeding site that they leave several years later when they become sexually mature adults. They then head to breeding sites within specific migration corridors. Depending on the geographical region, these corridors can lead some adults to migrate between oceanic and coastal zones whereas others remain exclusively in the coastal zone.

Although the turtles' open-ocean phase is estimated to last between 6.5 and 11.5 years, or even between 9 and 24 years depending on the study, little is known about this early phase of their life. In fact, no study has yet established the value and role of these juveniles in the ocean environment, and their numbers, movement and behaviour are poorly documented.

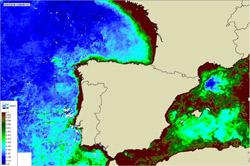

Animations showing Antioche's trajectories relative to sea level anomalies (altimetry), surface temperature (infrared) and water colour, derived from satellite data (click on each image to see the animation)

The tracked sea turtles' trajectories are at times influenced by ambient ocean conditions such as currents and sea level anomalies as well as by the seafloor terrain of the areas they swim through (see bathymetric data for Bambi and Antioche's journeys).

Turtles follow the main currents but sometimes move against the current. Sea turtles may use counter-currents to feed or to reduce their energy expenditure. These currents affect the animals' speed: upon reaching the Spanish coast, Bambi is pushed all the way down into the Bay of Biscay by a strong Navidad Current (a warm water stream from Portugal), for example, while Antioche rapidly reaches the Mediterranean Sea with the help of a strong surface current.

By staying close to the coast, where primary production is high, turtles can feed regularly.

By migrating southward, Antioche remains in areas with more forgiving winter temperatures (around 15°C). Bambi uses the same strategy and, while "stuck" at the bottom of the Bay of Biscay, survives winter temperatures without becoming stranded.

Turtles are able to cross both warm- and cold-core eddies, but tend to go around them. In the case of cyclonic eddies (with cold cores), turtles stay around the edges. This area has a higher concentration of food, which would explain turtle movements in some areas.